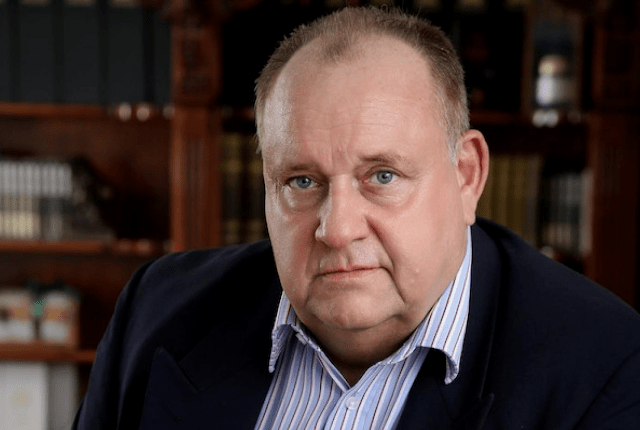

South Africa is facing a ‘pensions train smash’, says Magnus Heystek, director of Brenthurst Wealth Management, as a number of factors including the poor JSE, a weak economy and new regulations are set to collide.

Heystek said in a webinar on Wednesday (9 September), that this collision course is the result of a number of problems in the wider pensions industry which have been building for years.

He added that ordinary South Africans are starting to see the problems for themselves when looking at the return on their money.

“You can only hide bad news for so long and we have now had five to seven years of very poor return for most South African pension funds. So people are starting to wake up and are asking questions to their trustees and advisors, saying ‘what’s going on here? I am not making money’.”

Heystek said the funds are no longer able to rely on the ‘old chestnut’ of long-term gains, and that South Africans are increasingly choosing to step in and take control of their investments.

Prescribed assets

Heystek said that the issue of prescribed assets forms part of the bigger discussion around the pension industry – particularly the controls that government already has over pension funds in terms of regulation 28 of the Pensions Act.

He explained that regulation 28 prescribes where fund managers or advisors may or may not invest money.

“The salient point for many years now is that you are only allowed to invest 30% in offshore assets. The balance has to be invested in South Africa.”

Heystek said that many South Africans are only just beginning to realise how badly the JSE has done over the last seven to 10 years. “They are now starting to see that the rest of the world has had a tremendous bull market and (that) we are not part of it and have been left behind.”

While he noted that some stakeholders have started to pressure government to increase offshore investment, it was unlikely that this will happen. What is more likely is government’s increased interest in prescribed assets and pensions funds, he said.

Heystek said that in recent weeks the government has been ‘obfuscating’ how it plans to use prescribed assets and that it was only having discussions with pension funds.

“I don’t care what you call it, they have earmarked pension funds as a way to raise cheap capital to raise government-sponsored projects,” he said.

“They have quite clearly said that it is in order to get cheaper finance and cheaper finance means lower returns for investors, so it’s part of a broader discussion on regulation n 28, offshore investing, prescribed assets against the background of a stock market that has not grown very much.”

Money leaving

Heystek said that if you take out three or four shares – namely Naspers, Prosus, BAT and BHP Billiton – the JSE is actually down 30% over five years. “It is an astounding reflection of how bad the economy and the stock market is doing,” he said.

Citing his own data, he estimates that since president Cyril Ramaphosa took over in 2017, around R307 billion has left the JSE through foreign investment.

He added that money has been pulled from the stock market by these foreign investors for 23 of the last 24 months, at an average of about R10 – R12 billion a month. Heystek said that, compared to developed markets, South Africa no longer competes as an investment destination.

“There is a bigger problem here and we need to discuss this problem. I’m not saying panic and run for the hills – I am giving facts, and people must make up their own minds what they want to do with those facts.”

The ANC on prescribed assets

The ANC’s head of Economic Transformation, Enoch Godongwana, recently spoke to Alexander Forbes about the party plans for prescribed assets in South Africa.

Buzz around prescribed assets came about following the ANC’s 2017 policy conference – and subsequently its election manifesto in 2019 – where the party listed the introduction of ‘prescribed assets for pension funds to mobilise funds from financial institutions for social infrastructure’.

The announcement incited concerns from investors and members of retirement funds because of the possible implications it could have on investment portfolios and investment outcomes in the country.

Godongwana explained that the policy of prescribed assets came as a result of the challenges in South Africa, which have resulted in sub-optimal economic growth.

“Unemployment and the country’s recent credit rating downgrade to junk status are just some of the issues that have created this economic environment,” he said. “We have learnt that there are two main problems that have led to this precarious economic and social environment that we find ourselves in.”

Godongwana said that there is a high level of underdevelopment and poverty in the country that needs attention, and this is where infrastructure plays a critical role.

The central point of contention is how this infrastructure will be funded – and if prescribed assets would be introduced to force the private sector into participating in capital provision.

The possibility of prescribed assets was referred to as something ‘to be investigated’ and it is not something that could be instated without substantial consultation and a robust review process by the government.